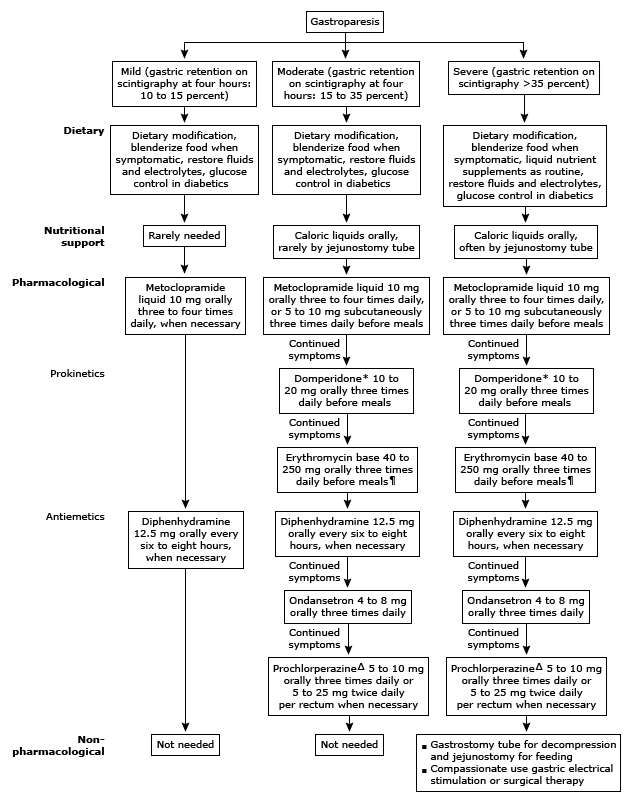

Gastroparesis

syndrome of objectively delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction and cardinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, early satiety, belching, bloating, and/or upper abdominal pain.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

- dietary modification,

- optimization of glycemic control and hydration, and

- in patients with continued symptoms, pharmacologic therapy with prokinetic and antiemetics

Dietary modification —

- considered first-line therapy in patients with mild gastroparesis, although in clinical practice it is associated with only a modest improvement in symptoms.

- Foods that are fatty, acidic, spicy, and roughage-based increase overall symptoms in individuals with gastroparesis

- Fat slows gastric emptying and nondigestible fiber (eg, fresh fruits and vegetables) require effective interdigestive antral motility that is frequently absent in patients with significantly delayed gastric emptying.

- Patients with gastroparesis à small, frequent meals four to five times a day that are low in fat and contain only soluble fiber.

- unable to tolerate solid food à meals should be homogenized, as gastric emptying of liquids is often normal even when emptying of solids is delayed

- avoid carbonated beverages à aggravate gastric distention

- Alcohol and smoking à avoided à decrease antral contractility and delay gastric emptying.

Hydration and nutrition —

- Recurrent vomiting and reduced oral intake may result in hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, and dehydration.

- Patients with gastroparesis can also develop micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies

- Hydration and vitamin supplementation should be provided orally in patients with mild gastroparesis.

Optimize glycemic control —

- Diabetes mellitus is a common cause of delayed gastric emptying

- acute hyperglycemia has been demonstrated to slow gastric emptying in patients with diabetes mellitus and healthy controls. In addition, hyperglycemia also attenuates the efficacy of prokinetic drugs.

In patients with diabetes, incretin-based therapies such as pramlintide (amylin analog) and GLP1 analogues or agonists (eg, liraglutide, exenatide) should be avoided as they can delay gastric emptying.

In contrast, dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors (eg, vildagliptin, sitagliptin) do not affect gastric emptying.

Prokinetics —

- for patients who continue to have symptoms of gastroparesis despite dietary modification.

- Prokinetics à increase the rate of gastric emptying and

- should be administered 10 to 15 minutes before meals with an additional dose before bedtime in patients with persistent symptoms.

Metoclopramide —

- first-line therapy for gastroparesis.

- dopamine 2 receptor antagonist, a 5-HT4 agonist, and a weak 5-HT3 receptor antagonist

- improves gastric emptying by enhancing gastric antral contractions and decreasing postprandial fundus relaxation.

- approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of gastroparesis for no longer than 12 weeks unless patients have a therapeutic benefit that outweighs the risks.

- side effects à anxiety, restlessness, and depression, hyperprolactinemia, and QT interval prolongation. Extrapyramidal side effects, including dystonia in 0.2 percent of patients and tardive dyskinesia in 1 percent of patients, have led to a black box warning

- Initiate treatment with a low-dose liquid formulation (eg, 5 mg, 15 minutes before meals and at bedtime), titrating up to identify the lowest effective dose. Many patients can tolerate treatment with up to 40 mg of oral metoclopramide per day, in divided doses

- can also be administered by intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous routes.

- Metoclopramide nasal spray has been demonstrated to reduce symptoms of gastroparesis in diabetic women with gastroparesis, but not in men

Domperidone —

- In patients whose symptoms fail to respond to metoclopramide or with side effects to metoclopramide, we use domperidone at a dose of 10 mg three times daily and increase to 20 mg three times daily with an additional dose at bedtime, if symptoms persist.

- a dopamine 2 antagonist

- efficacy of domperidone in diabetic gastroparesis is likely similar to that of metoclopramide

- domperidone may increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmias. Domperidone should be withheld if the corrected QT is >450 ms in men and >470 ms in women. Domperidone can cause hyperprolactinemia

Macrolide antibiotics

Erythromycin —

- a motilin agonist,

- induces high-amplitude gastric propulsive contractions that increase gastric emptying

- also stimulates fundic contractility, or at least inhibits the accommodation response of the proximal stomach after food ingestion.

- Patients who fail to respond to a trial of metoclopramide and domperidone should be treated with oral erythromycin (liquid formulation, 40 to 250 mg three times daily before meals)

- Oral erythromycin should be administered for no longer than four weeks at a time, as the effect of erythromycin decreases due to tachyphylaxis.

- Use of higher doses (eg, 250 mg, compared with 40 mg) may be more likely to cause abdominal pain or induce tachyphylaxis.

- Intravenous erythromycin should be reserved for acute exacerbations of gastroparesis in which oral intake is not tolerated.

Azithromycin —

- Azithromycin has a longer half-life, and fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects and drug interactions as compared with erythromycin.

- However, azithromycin is a weak inhibitor of CYP3A4 and like erythromycin may prolong cardiac repolarization and the QT interval, increasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmias and torsade de pointes.

- There are no randomized trials directly comparing azithromycin and erythromycin in patients with gastroparesis.

Cisapride —

- a 5HT4 agonist,

- stimulates antral and duodenal motility and accelerates gastric emptying of solids and liquids

- Although cisapride is better tolerated than metoclopramide, its use has been associated with important drug interactions with medications metabolized by the cytochrome P450-3A4 isoenzyme (eg, macrolide antibiotics, antifungals, and phenothiazines) resulting in cardiac arrhythmias and death

- If prescribed, cisapride should be administered to patients who have failed a trial of all other prokinetics, at a dose of 10 to 20 mg four times daily, one-half hour before each meal and at bedtime.

Antiemetics —

- Antiemetics have not been studied in the management of patients with gastroparesis, and their use in gastroparesis is based on their efficacy in controlling nonspecific nausea and vomiting and in chemotherapy-induced emesis.

- persistent nausea and vomiting despite prokinetics à antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine 12.5 mg orally or intravenously every six to eight hours as needed) and

- in patients with persistent symptoms, 5HT3 antagonists (eg, ondansetron 4 to 8 mg orally three times daily).

REFRACTORY SYMPTOMS

- refractory symptoms à despite dietary modification, prokinetics, and antiemetics,

- re-evaluate compliance with dietary modification and pharmacotherapy

- placement of a jejunostomy and venting gastrostomy tube for enteral nutrition and decompression, respectively.

- parenteral nutrition only in patients who cannot tolerate enteral nutrition despite concomitant pharmacotherapy.

- gastric electrical stimulation only in patients with gastroparesis with intractable nausea and vomiting despite medical therapy for at least one year.

- Gastric electrical stimulation has been demonstrated to improve symptom severity and gastric emptying in patients with diabetic, but not idiopathic or postsurgical gastroparesis. In the United States, the gastric electrical neurostimulator (Enterra Therapy system) has been approved as a humanitarian exemption device for diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE EXACERBATIONS

- erythromycin 3 mg/kg intravenously (IV) every eight hours.

- patients who fail IV erythromycin with subcutaneous metoclopramide (5 to 10 mg three times daily).