Inhaled glucocorticoids

Inhaled glucocorticoids (commonly called inhaled steroids or ICS) are considered the agents of choice in all patients with persistent asthma according national and international guidelines

ICS have fewer and less severe adverse effects than orally-administered glucocorticoids, and they are widely used to treat asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

However, there are concerns about the systemic effects of ICS, particularly as they are likely to be used over long periods of time, in infants, children, and older adults. The safety of ICS has been extensively investigated since their introduction for the treatment of asthma 30 years ago

- Beclomethasone HFA (40mcg per puff, 80 mcg per puff)

- Budesonide DPI (100 mcg per inhalation, 200 mcg per inhalation)

- Ciclesonide HFA (100 mcg per inhalation, 200 mcg per inhalation)

- Flunisolide MDI (80 mcg per puff)

- Fluticasone propionate HFA ( 50 mcg per puff)

- Mometasone DPI (100 mcg per inhalation, 200 mcg per inhalation)

DPI: dry powder inhaler; HFA: hydrofluoroalkane propellant metered dose inhaler

Efficacy —

- Regular treatment with inhaled glucocorticoids

- reduces the frequency of symptoms (and the need for inhaled bronchodilators),

- improves the overall quality of life, and

- decreases the risk of serious exacerbations for patients with asthma.

- In addition, by reducing airway inflammation, this therapy alters a basic property of the airways in asthma, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, reducing their exaggerated sensitivity to any and all triggers of asthma.

Representative studies demonstrating the efficacy of inhaled glucocorticoids include the following:

●A multicenter, double-blind trial randomly assigned over 7000 patients with mild persistent asthma to treatment with low-dose inhaled budesonide (400 mcg once daily) or placebo for three years

budesonide à

- decreased risk of a severe asthma exacerbation

- better pulmonary function and experienced fewer days with symptoms.

Not all patients with asthma are responsive to inhaled glucocorticoid therapy. Studies suggest that up to 35 percent of patients may not experience improvements in FEV1 or bronchial hyperresponsiveness

patients with mild asthma who smoke cigarettes appear relatively resistant to the effects of low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids.

Initial dosing —

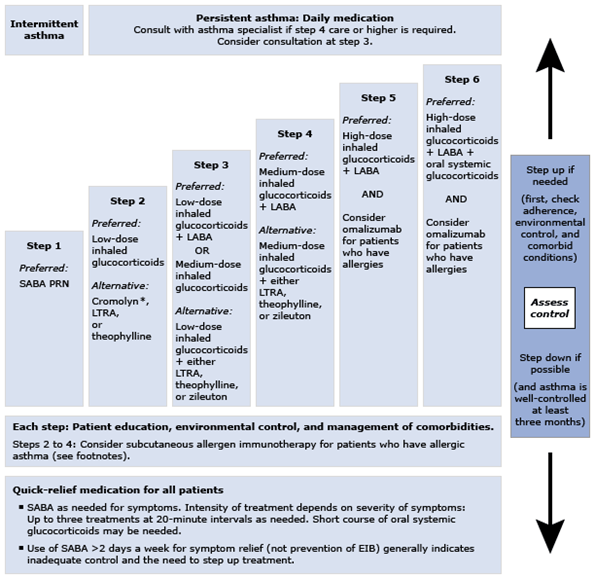

low-dose range, corresponding to Step 2 treatment

Among the low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids, mometasone is approved for once-daily dosing.

The other inhaled glucocorticoids have traditionally been administered twice daily, although it is likely that they can be used once daily in many patients with mild asthma, which might improve compliance.

More evidence supports the safety of budesonide during pregnancy than for the other inhaled glucocorticoids.

Delivery devices and spacers —

Inhaled glucocorticoids are available via MDI, breath-actuated MDI, dry powder inhaler (DPI), soft mist inhaler, and as a solution for nebulization.

Use of a valved holding chamber (“spacer”) device with MDI glucocorticoids is recommended in order to maximize medication delivery to the bronchi and to minimize oropharyngeal deposition.

Spacers are not used with DPIs, SMIs, or breath-actuated MDIs

Side effects —

Oral candidiasis and dysphonia (hoarse voice) are the most common side effects of low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids.

EFFECTS OF LOCAL DEPOSITION

Side effects due to the local deposition of inhaled glucocorticoid in the oropharynx and larynx may occur. The frequency of complaints depends on the specific drug, dose, frequency of administration, inhaler technique, and the delivery system used.

Dysphonia —

Reported incidences vary from 1 to 60 percent, depending on the patient population, device, dose, length of observation, and manner of data collection

The mechanism of ICS-associated dysphonia may involve factors such as myopathy of laryngeal muscles (manifest as incomplete closure or bowing of the vocal cords on adduction), mucosal irritation, and laryngeal candidiasis

Dysphonia is sometimes reduced by using a spacer with the MDI, although results are variable

Topical candidiasis —

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush) à particularly elderly patients, patients taking concomitant oral glucocorticoids or antibiotics.

For patients using MDIs, large volume spacer devices may protect against thrush by reducing the amount of drug deposited in the oropharynx.

In addition, rinsing the mouth and throat with water and expectorating the rinsate after use of all forms of ICS is preventative.

reported in up to 15 percent of patients complaining of dysphonia during ICS therapy.

Contact hypersensitivity —

Allergic contact dermatitis has occasionally been described due to ICS, particularly budesonide. An erythematous, eczematoid eruption is typically noted around the mouth, nostrils, or eyes.

Other — Cough and throat irritation, sometimes accompanied by reflex bronchoconstriction, may occur

SYSTEMIC ADVERSE EFFECTS

The addition of intranasal glucocorticoids to high-dose ICS (eg, in patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma) likely increases the systemic exposure to glucocorticoids, although the contribution to adverse effects has not been specifically quantified

Adrenal suppression —

Systemic administration of glucocorticoids causes hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression by reducing corticotropin (ACTH) production, which reduces cortisol secretion by the adrenal gland.

The degree of HPA suppression is dependent on dose, duration, frequency, and timing of glucocorticoid administration.

The risk of symptomatic adrenal suppression or acute adrenal crisis by ICS therapy is small, particularly when the doses used are within the recommended ranges.

To screen for adrenal insufficiency, the first step is measurement of serum cortisol in the morning (eg, 8 AM). Because cortisol normally peaks in the morning, a low level suggests adrenal insufficiency. The results are interpreted as follows:

●A morning cortisol <3 mcg/dL, suggests probable adrenal insufficiency. This is sufficient to make the diagnosis if the patient is symptomatic.

If the patient is asymptomatic, an ACTH stimulation test should be performed to evaluate further for adrenal insufficiency.

●A morning cortisol 3 to 10 mcg/dL is inconclusive. In most cases, the child should be further evaluated with an ACTH stimulation test

●A morning cortisol level >10 mcg/dL is reassuring, but does not completely exclude adrenal insufficiency. Further evaluation with an ACTH stimulation test may be appropriate if the patient is symptomatic.

When the ACTH stimulation test is performed, the guideline recommends using the low-dose of ACTH (1 mcg intravenously), with measurements of cortisol at baseline and 30 minutes at a minimum.

A peak cortisol level below 18 mcg/dL is consistent with adrenal insufficiency.

Lung infection —

●Pneumonia – Data are somewhat mixed regarding the risk of pneumonia among patients with COPD or asthma taking ICS, although a small increase in risk is usually reported

●Tuberculosis – In a nested case-control study that included over 400,000 patients with asthma or COPD (564 cases of tuberculosis), the risk of tuberculosis was slightly increased among all users of ICS (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.18-1.56), particularly those using doses equivalent to fluticasone propionate 1000 mcg per day or more (RR 1.97, 95% CI 1.18-3.3)

●Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection – A separate study raised the possibility of an increased risk of non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease among COPD patients treated with ICS. In a population-based case control study, the adjusted odds ratio for NTM disease in patients with underlying COPD who were ever treated with ICS was 19.6 (95% CI 9.7-39.6) compared with 7.6 (95% CI 3.4-16.8) for those not treated with ICS [69].

Ocular effects — Systemic glucocorticoids can contribute to increased intraocular pressure and increased risk of cataract formation. A few studies have examined whether ICS can have similar effects.

Intraocular pressure — Conflicting data have been reported regarding whether ICS are associated with an increased risk of ocular hypertension

The investigators suggested that ocular pressure should be monitored in older adults with a family history of glaucoma who are using high dose ICS.

Cataracts — The use of systemic glucocorticoids is a definite risk factor for the development of posterior subcapsular cataracts. In contrast, the risk with ICS use is less clear, since the majority of studies could not control for the confounding use of systemic glucocorticoids

Skeletal effects — The potential skeletal effects of ICS include growth deceleration in children and increased risk for osteoporosis in both adults and children.

Growth deceleration —

Despite concerns that ICS might be associated with growth deceleration in children, the effect of ICS on adult height appears small based on a number of studies described below.

Asthma itself (as with other chronic diseases) has been associated with a deceleration of growth velocity, which is most pronounced with severe disease.

However, asthma is also associated with a delayed onset of puberty, such that asthmatic children may continue to grow over a longer period of time. Further research is needed to determine whether individual ICS have differing effects on growth and to better define the long-term effect of ICS on adult height.

Osteoporosis and fracture risk in adults —

The effects of oral glucocorticoids on bone metabolism and osteoporotic vertebral and rib fractures are well known. However, studies of the impact of ICS on the risk of osteoporosis and the more clinically relevant outcome of osteoporotic fracture have yielded conflicting results in adults.

Until the risks for osteoporosis and fracture are better defined for ICS therapy, measures to decrease the likelihood of osteoporosis are warranted particularly in patients using high dose ICS

Adult patients receiving chronic therapy with inhaled glucocorticoids who have a moderate risk of osteoporosis should undergo bone density measurement to assess the need for preventive therapy.

Bone health in children — A dose-dependent reduction in bone formation with use of ICS has been demonstrated in

Other potential concerns

●Skin changes and bruising –

Topical and oral glucocorticoids cause thinning of the skin, telangiectasia, and easy bruising. These effects may result from loss of extracellular ground substance within the dermis, due to an inhibitory effect on dermal fibroblasts.

There are reports of increased skin bruising and purpura in patients using high doses of inhaled beclomethasone

●Myopathy –

As mentioned above, ICS can cause dysphonia resulting from a localized myopathy of the vocal cords due to local deposition.

Whether systemic absorption of ICS can cause more generalized myopathy is less clear.

●Psychiatric effects – There are various reports of psychiatric disturbance, including emotional lability, euphoria, depression, aggressiveness, and insomnia, associated with use of ICS.

●Pregnancy – Based on extensive clinical experience, ICS appear to be safe in pregnancy, although controlled studies have not been performed for obvious reasons.

●Lipid metabolism –

Minimal to no effect of ICS has been found on lipid metabolism.

MEASURES TO MINIMIZE SYSTEMIC SIDE EFFECTS

A number of measures may help to minimize the risk of adverse effects from inhaled glucocorticoids (ICS) therapy.

General measures

●Step down treatment to the lowest possible dose of ICS that maintains symptom control

●Optimize compliance with ICS therapy to maintain disease control

●Optimize delivery: use spacer with metered dose inhalers (MDI), use spacer and facemask with MDIs in young children

●Advise patients to rinse mouth and pharynx, and then expectorate the rinsate after using all ICS

●Evaluate and treat for complicating features of asthma or COPD

●Add long-acting bronchodilator as indicated by guidelines

●Maximize nonpharmacologic treatment (eg, trigger avoidance, vaccination against respiratory infection)

Spacers and valved holding chambers —

Spacers and valved holding chambers, which are used with MDIs, are designed to improve delivery to the lower airway and reduce upper airway deposition.

Use of a large volume spacer device with a MDI can increase the amount of drug delivered to the lung to about 20 percent [

Medication interactions — Clinicians should use caution when combining high-dose ICS with potent CYP450 3A4 inhibitors, such as clarithromycin, itraconazole, and ritonavir, as these agents may enhance the systemic effects of ICS